How We Care for What Time Cannot Return – and Why It Matters

The History and Theory of Conservation and Restoration

Restoration as an Artistic Act

The history of restoration and conservation is not merely a history of preservation, but also one of intervention, interpretation, and creative shaping. Between the aspiration to safeguard the past and the impulse to recreate it, there has long existed a field of tension—a discourse that leads deeply into aesthetic and ethical questions.

This field is by no means separate from art history—on the contrary: it is just as central for art historians as it is for anyone engaging with art. Every act of viewing, every interpretation of an artwork, is always also a reflection on its current material state—and thus on its history of restoration.

The question of what constitutes “authenticity,” how much intervention is permissible—or even necessary—and who ultimately decides what is preserved, concerns not only conservators, but all those who view, study, or exhibit art. That is why I am writing this.

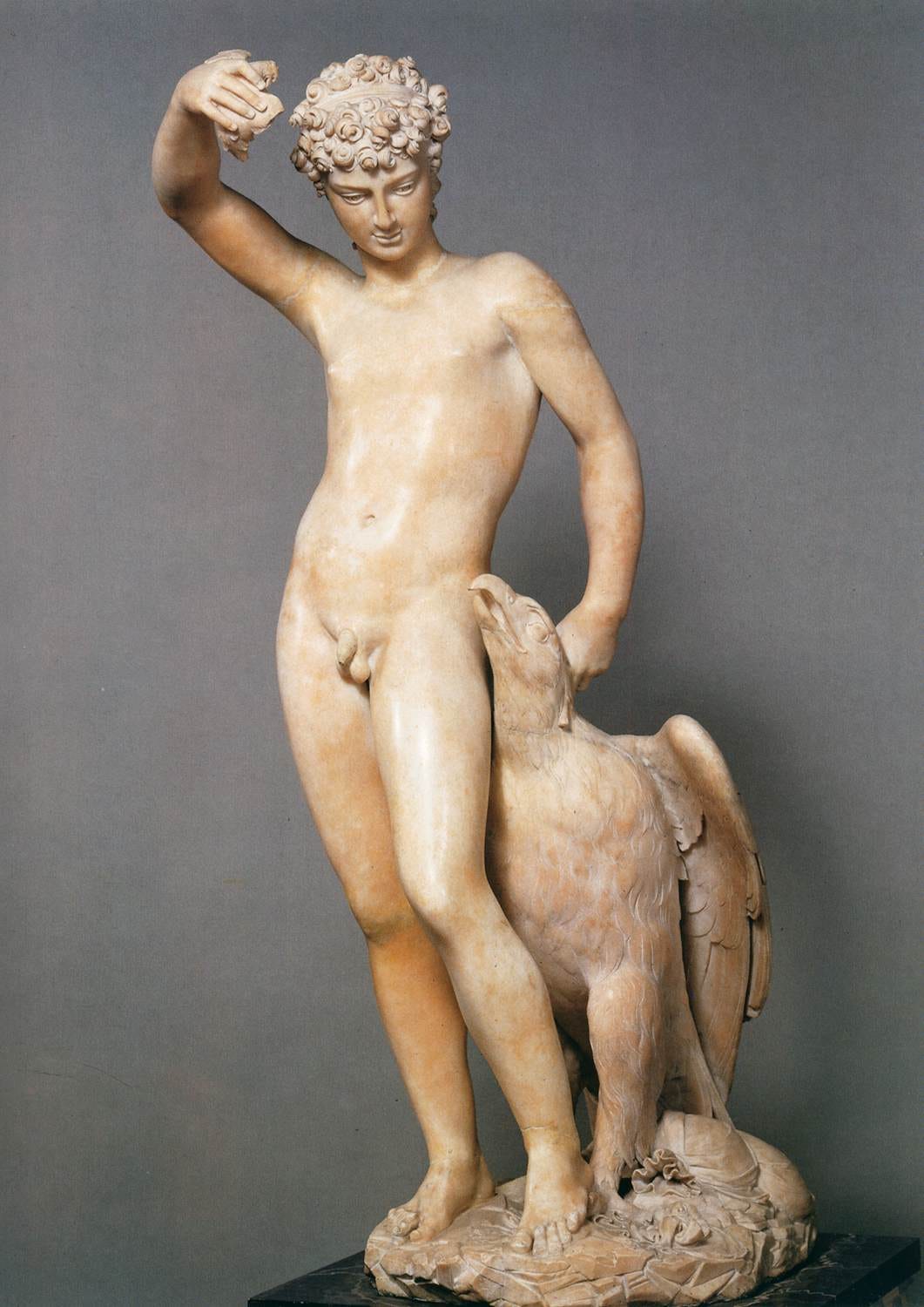

A particularly revealing example is provided by the Italian sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini. In his autobiography, he recounts how Grand Duke Cosimo de’ Medici, his principal patron from 1545 onward, showed him a Greek marble sculpture of a boy, of which only the torso and legs had survived. Cellini agreed to “(...) restore it and add the head, arms, and feet.” He went on: “I will also make an eagle for it, so that the figure may be called a Ganymede.” (See: Heinrich Conrad (trans.). The Life of Benvenuto Cellini Written by Himself. Munich, 1913, pp. 572f.)

What Cellini does here is more than mere reconstruction—it is an act of creative appropriation and expansion. The damaged fragment becomes a canvas for a new artistic vision, transformed into the mythically charged figure of Ganymede. Well into the 19th century, such an understanding of restoration was widespread: restoration was seen as a form of artistic practice, as a continuation of an idea, not as a deferential retreat before the historical artifact.

It was not the object itself that was restored, but what it could have been. The artistic idea was placed at the center—not the historical document.

At this point, the distinction between production aesthetics and reception aesthetics becomes crucial: Is the artwork about the original artist’s intention—or about its effect on the viewer?

The contemporary artist Tobias Rehberger has expressed this shift in perspective succinctly in an interview with Art Magazine. When asked, “What does good art mean to you?” he replied:

“That through it, you come across things that have more to do with yourself than with what the artist intended.” (Originally: „Dass man durch sie auf Sachen kommt, die mehr mit einem selbst zu tun haben, als mit dem, was der Künstler wollte.“)

Such a statement can equally be applied to the restored artwork: the boundary between preservation and interpretation, between original and addition, has often been—and still is—fluid. And it is precisely this ambiguity that constitutes the central challenge of any theory and practice of restoration.

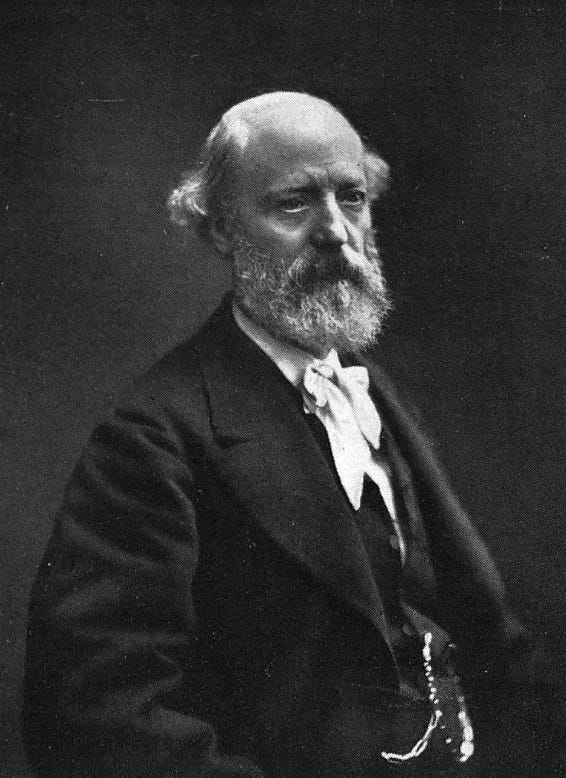

This understanding of restoration as a creative act of completion continued to resonate in nineteenth-century architectural theory. The main proponent of this so-called “restoration according to ideas” (restauration selon une idée) was the French architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879). He restored numerous significant Gothic buildings in France, including the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris and the city walls of Carcassonne.

Yet his approach was far from conservative in the modern sense: Viollet-le-Duc did not aim to reconstruct the historical state of a building, but rather to realize his own vision of what Gothic architecture ought to have looked like, according to its underlying idea. His goal was not the preservation of what had historically become, but the stylistic perfection of its original form.

This approach, however, was not without controversy—even in the nineteenth century. As early as 1805, Johann Dominik Fiorillo, considered one of the founding figures of academic art history in Germany, had pointed to the fundamental fallacy behind such thinking. In contrast, he argued that a work of art is inseparably bound to its concrete historical form—and therefore cannot be arbitrarily reconstructed.

One of the most influential critics of restorative interventions based on the principle of stylistic ideal form was the English painter, art theorist, and Oxford professor John Ruskin. In his seminal work The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), Ruskin passionately argued against any form of creative restoration.

Rather than focusing on the stylistic unity of a building, he turned his attention to its materiality—to the traces of aging, the patina, the scars of time. For Ruskin, any act of restoration was a kind of falsehood, attributing to the object a condition it never truly possessed. Instead, he advocated for a careful and respectful maintenance that would protect the historical substance without altering its character.

“Restoration means the most total destruction which a building can suffer: a destruction out of which no remnants can be gathered: a destruction accompanied with false description of the thing destroyed.”

(John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, New York: Dover, 1889. Reprint of the 2nd edition from 1880; original text from 1849.)

With Ruskin, a decisive paradigm shift begins: a move away from the idea of “completing” artworks toward the recognition of their history and incompleteness. The traces of time are no longer seen as flaws, but as meaningful signs—part of the artwork itself.

This development culminated in the 20th century in the attempt to establish a distinct scholarly discipline: the theory of conservation and restoration.

One of the first major systematic frameworks was developed by the Italian art historian Cesare Brandi, who published his treatise Teoria del restauro in 1963. In this work, Brandi formulated a theory explicitly focused on the visual arts, but which extended far beyond practical guidelines. His aim was to analyze the aesthetic, historical, and material dimensions of a work of art in their inherent tensions—and to derive from them criteria of responsibility for conservation practices.

Brandi’s approach was revolutionary insofar as he no longer sought to reconstruct a lost ideal state, but rather aimed to respect the artwork in its historical becoming. According to Brandi, every restoration must do justice both to the aesthetic unity and to the historical truth of the object—and it must not blur the difference between original and addition, but instead keep it visible.

These considerations became foundational for later international standards—such as the Venice Charter (1964), which was adopted one year after Brandi’s publication and remains a key reference document in the field of heritage preservation.

Despite these developments, the discipline of conservation and restoration is still undergoing a process of scientific consolidation today. Although specialized degree programs, research institutions, and international committees exist worldwide, an independent, universally recognized science of conservation/restoration has yet to be fully established. The development of theoretical foundations that go beyond craft and technical norms remains a challenge—as does the question of how to methodically and responsibly handle the complexity of material, meaning, context, and reception.

Scientific theories dealing with the preservation of cultural heritage may focus either on the heritage as a whole or on specific areas within it. What unites them is the goal of systematically describing the properties of an object that are relevant for its preservation—and from this, deriving justified courses of action for conservation or restoration.

At the core is not only the material substance but also the meaning that a cultural asset holds for the present and the future. It is precisely here that it becomes clear that this field is by no means a “subsidiary” technical discipline—but rather a central part of art historical and societal engagement with our cultural heritage.

Moreover, the scientific consolidation of this field is of extreme importance for art historians and other specialists, since a scientifically sound interpretation of cultural heritage is only possible if the results of conservation and restoration are themselves developed scientifically. In other words, the concepts and outcomes must have the character of a scientific statement. This includes, for example, the description of manufacturing techniques as well as the historically evolved state of preservation of the cultural assets, from which the possibilities and consequences of intervention can be deduced.

Conservation and Restoration: On the Theory of Preserving Cultural Heritage

The goal of any preservation effort must be the transmission of meaning. Cultural heritage objects are documents—they convey something about a past that can no longer be directly experienced. As documents, they present a coherent offering of meaning. Artworks, too, are documents, but at the same time bearers of aesthetic meanings that are highly subjective in their reception. Preserving this capacity for subjective transmission of meaning is the foremost objective of conservation and restoration.

But what exactly is meaning—and how can it be preserved?

To answer this question, the process of perception must be considered. Cultural heritage consists of sets of signs, comparable to literary texts or musical scores. These signs contain potentially information-bearing, materially encoded elements that can be read and cognitively processed. This results in a subjective meaning—a mental state. The consequence for preservation is crucial: meanings are subjective and immaterial—and therefore cannot be conserved. Only the material as the carrier of signs can be preserved—that is, every prerequisite that makes meaning possible in the first place.

The theory presented here regards works of visual art as text-analogous works whose nonverbal sign systems can be deciphered through image semiotics. For conservation and restoration, it suffices to consider the signs according to their classes. The aesthetically effective part of an artwork consists of three classes of signs: form, color (color scheme), and material character. The latter is often overlooked, although it includes additional documentarily effective signs. Only the interplay of form, color, and material character determines the aesthetics of a painting.

Conservation and restoration therefore work on the data carrier—they essentially perform data rescue. The signs of an artwork convey information about its aesthetics, the time of creation, the time after its production, and the history of techniques. Aesthetics and the time of creation are inseparably linked. Secondary historical information is also taken into account; however, in cases of conflict, primary information takes precedence.

Recent theoretical expansions emphasize that the material character created by the artist—such as glossy or matte surfaces—is part of the work. This also includes functional components and natural aging effects.

On the Methodology and Prioritization of Conservation and Restoration

At the core of all conservation efforts lies the preservation of the existing material—not its alteration. Conservation is therefore always the first and foremost step, because only what is materially present can remain legible or be made legible again. Restoration, on the other hand—although it seeks to improve or restore the legibility of an artwork—is secondary. Every restorative intervention is more invasive, produces aesthetic changes, and inevitably involves a certain degree of subjectivity. While good conservation is recognizable by its invisibility, restorative interventions are immediately perceptible and inevitably influence the reception of the original.

Conservation protects the “text” of the artwork—and this is inseparably linked to its material. When material is lost, information is lost as well. From this follows a clear priority: conserve before restoring!

In practice, three central types of measures are distinguished: Preventive conservation aims to prevent damage and loss from occurring in the first place. It focuses on the object's environment—such as controlled climate conditions, gentle lighting, or careful storage. Its guiding principle is the well-known adage: prevention is better than cure. Curative conservation, on the other hand, intervenes directly on the object. It becomes necessary when damage has already occurred—such as consolidating flaking paint layers—and aims to prevent existing losses from spreading. Finally, Restoration specifically supplements areas to improve the legibility of the artwork: through retouching, removing dirt or altered varnishes, and eliminating later overpaintings. However, all these measures are profound and irreversible—they cannot undo loss, only conceal it.

In dealing with restoration materials, a clear principle applies: the less invasive the intervention, the fewer the side effects—and the more original information is preserved. Additions that are irreversible or that cover the original surface impair legibility and jeopardize future restorations. It becomes particularly problematic when these additions are no longer recognizable as such: this risks a partial forgery, as the original can no longer be clearly distinguished from what has been added.

Two approaches are available to ensure the distinguishability of additions: either materials or techniques are chosen that can be scientifically clearly differentiated from the original—or retouching methods are used that remain clearly visible even to the naked eye.

A particular area of tension lies in the treatment of dirt and varnish. Dirt can significantly interfere with the perception of a painting’s colors—yet it may also contain historical information. The handling of varnishes is even more complex: if the varnish was applied by the artist, it is part of the original aesthetic intention—but it is also subject to natural aging. Foreign varnishes applied later—such as those from subsequent restoration practices—do not belong to the artwork. Nevertheless, varnish is often interpreted as a protective layer. From a conservation perspective, however, this attribution is problematic: if protection were truly its main function, varnish would be considered a conservation measure. Since aesthetic effect usually takes precedence, this contradiction remains unresolved—and the claimed protective function is methodologically irrelevant.

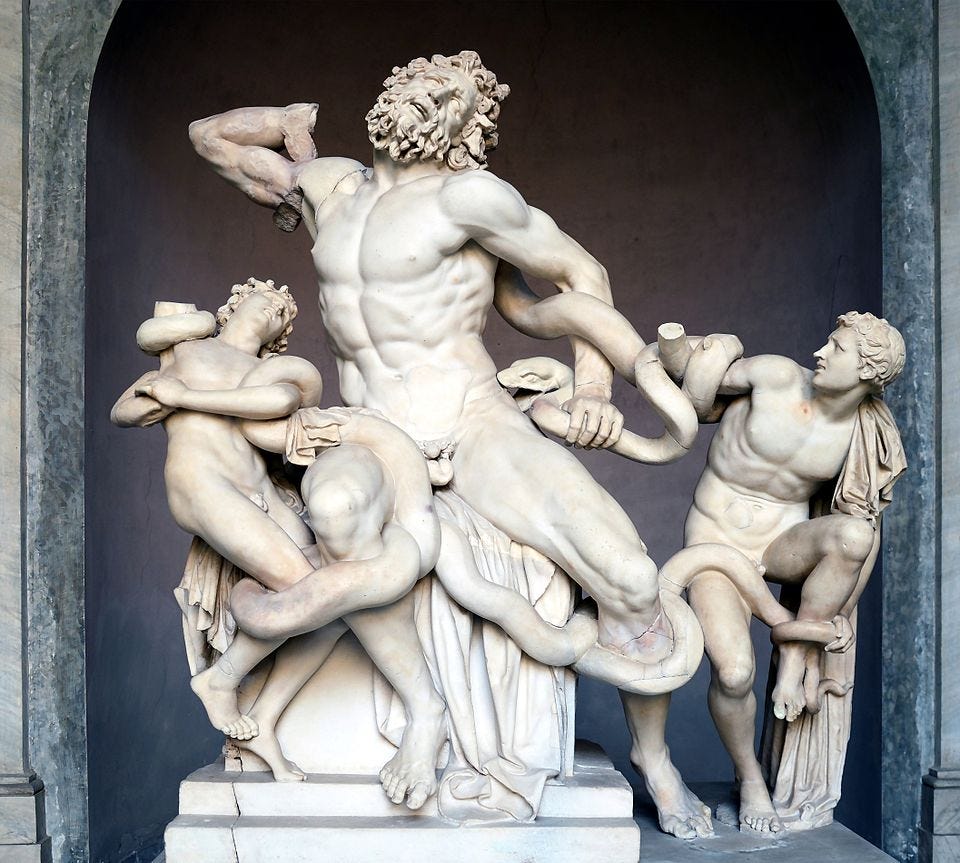

Finally, restoration science clearly distinguishes between natural and anthropogenic changes. The natural aging of an artwork—caused by light, climate, or time—is unavoidable. Color changes may be aesthetically painful but are irreversible and must be accepted as part of the work’s history. Often, a mental reconstruction of the original state suffices here, without attempting physical reversal. Anthropogenic changes, such as later overpaintings or interventions, raise much more complex questions. They can hinder readability but may themselves have historical or artistic value. This leads to a valuation problem: which traces of history are worth preserving—and which may (or must) be removed?

Herein lies the greatest conflict potential of restoration: in a medium that leaves meanings open and in which every evaluation inevitably introduces subjectivity, it is hardly possible to establish binding criteria for dealing with historical layers. For closed historical documents—such as inscriptions or written sources—standards are clearer: only the derived achievement is evaluated, not the text itself. But with artworks, the rule is: not every trace is equal. Treating everything the same leads to arbitrariness—and precisely for this reason, measures that indiscriminately remove historical traces must be fundamentally excluded.

Thank you very much for reading; I hope this was helpful.